Tips on Making Wild Teas

Let's start with flowers. Since the source of flavors from flowers reside on the flower's surface you can use blossoms either straight off the plant or in a dried form. Most flowers will have the best flavor right at opening which usually means mornings unless they're a night-bloomer. Pick flowers before the day's sun has baked away all their flavor. If they're to be dried make sure any morning dew or rain has evaporated away and then hang the flowers someplace to dry. Don't use a dehydrator as that'll force out much of the flower's delicate flavors...though your kitchen will probably smell great. To make flower tea, bring water to a boil, let it cool five minutes, pour it over the flowers, then let steep at least 5 minutes in a covered pot or mug (again to keep the flavors trapped in the tea).

Next up, leaves. Making tea from leaves requires aging the leaves first for best results. Remember, plant cells are enclosed in a rigid cell wall which among its duties is to prevent stuff inside the plant cell from getting out just as much as stopping stuff from outside the cell getting in. If you steep fresh leaves most of the flavors and medicinal components will remain trapped inside the leaves' cells rather than entering your tea. However, when a plant get's harvested or otherwise killed a set of enzymes inside the cell are activated and begin chewing holes in the cell wall. This is part of the mechanism used by plants to return their nutrients back to the soil when they die. After about two weeks the cell wall will have assorted holes so now when the leaves are soaked all their wonderful goodness will flow into the tea. To make tea from leaves, bring water to a boil then pour it over the dried and somewhat crumbled leaves, then let steep 3-10 minutes in a covered pot or mug. Strain out the leaves before drinking.

If you do want what's inside the leaves without the time needed to wait you must chop and grind the leaves up. This ruptures the cell walls, releasing the cellular compounds. The vitamin C found in pine needles or cleavers falls into this category. When one is suffering from scurvy one can't wait two weeks for the necessary vitamin C!

Fruit teas such as rose hip or Turk's cap fruit are similar to leaf teas in that dried fruits will give a better flavor than fresh fruits. Also, since the fruits are tougher than leaves go ahead and actually boil the fruits in the water for about five minutes then let everything cool down to a drinkable temperature. I eat the fruit afterwards but be sure to remove any rose seeds from the rose hips before drying as the fine hairs on rose seeds can cause irritation at the end of their journey through your digestive system.

Root and bark are usually the toughest parts of plants so they require vigorous boiling rather than just steeping in hot water. Boil roots/bark at least 10 minutes then remove from heat and let the tea steep and cool at least another 10 minutes before straining out the plant matter. As mentioned earlier, it's best if the plant has time to "age" a few weeks so that enzymes can break down the cell walls. If you need it right away you'll have to crush/grind the roots or bark.

Flowers for Tea:

Basswood, Barbados Cherry, Blackberry, Bottlebrush, Sweet Clover, Red Clover, White Clover, Dandelion, Dewberry, Elderberry, Goldenrod, Heal's All, Henbit, Horsemint/Lemon Beebalm, Mallow, Mullein, Parsley Hawthorn, Passionvine, Pineapple Weed, Rose, Milk Thistle, Turk's Cap, Violet, Wild Bergamot, Yarrow

Leaves for Tea:

Balloon Vine, Blackberry, Bottlebrush, Burdock, Carolina Bristle Mallow, Cleavers, Dandelion, Dewberry, Ginkgo, Goldenrod, Heal's All, Henbit, Yaupon Holly, American Holly, Horsemint/Lemon Beebalm, Lizard's Tail, Pine Needles, Loquat, Lyreleaf Sage, Mullein, Parsley Hawthorn, Passionvine, Pimpernel, Pineapple Weed, Sassafras, Stinging Nettle, Bull Thistle, Milk Thistle, Violet, Yarrow

Roots, Barks, Fruit, and Mushrooms for Tea:

Blackberry, Buffalo Gourd, Burdock, Chicory, Dandelion, Dewberry, Honey Locust seedpods, Horsetails, Indian Strawberry, Lizard's Tail, Mallow Seeds, Mayhaw, Reishi Mushroom, Turkey Tail Mushroom, Parsley Hawthorn Fruit, Rose Hips, Sassafras, Slippery Elm, Sumac Berries, Bull Thistle, Milk Thistle, Turk's Cap Fruit, Willow

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.

Making Maple Syrup & Sugar

First, a little plant biochemistry. The sugar in maple sap is used by the tree as building blocks for making new leaves. This means the sugary sap starts flowing in late winter when the tree starts making the leaf buds. Up north, the tree "wakes up" and begins pumping sap up to its branches when nights are still below freezing but daytime highs are in the mid-40s. This is when you need to tap your tree. In southern climates knowing when the sap flows is trickier. I suggest you drill a 1/4" hole into your tree at a slight upwards angle 3" into the tree on New Year's Day and then watch for sap to begin leaking out. Drill this hole on the south (warmest) side of the tree about 3 feet off the ground, just as you would place a tap (aka "spile"). I wouldn't put a tube or anything in it other than maybe a cotton ball that had been treated with the bleach solution. Just keep an eye on the hole and see if it starts weeping.

Traditional maple tree taps are called spiles and can be ordered on-line from various sources. You can also make your own spiles from PVC tubing, Tygon tubing, plastic pen bodies, hollowed-out pieces of elderberry, bamboo, etc. Just make sure the hole you drill will hold the spile tightly. If the hole is too big you can pack the opening with softened wax. The spile should be cut at an angle with the longer part of the spile up against the top of the hole. Sap flows into the hole from the bottom (duh), so you don't want to plug the bottom of the hole. Sterilized soda bottles make great collectors as the small top keeps crap out of the sap. Traditional sap buckets have hinged cover to do the same thing (crap protection).

You need a maple tree at least 12" in diameter to tap. Drill the tap hole(s) on the south-facing side of the tree about three feet off the ground. If the tree is more than 20 inches in diameter you can add a second spile, and if it's greater than 27 inches you can have three spiles. The tap holes are drilled 3 inches deep at a slight upward angle. Spiles will be either 5/16 inches or 7/16 inches in diameter, so use the corresponding drill bit. Pound the spile into the hole and hang your bucket from the little notch on the spile.

IMPORTANT: Wash all your drill bits and spiles with a bleach solution before they enter the tree to avoid infecting the tree with fungus or bacteria! Use a 1:10 bleach to water solution (example: 1 teaspoon bleach in 9 teaspoons of water). Let any plug-dowel soak in freshly-made bleach solution for about 15 minutes before inserting it into the hole. Soak-time for spiles and drill bits ranges from 2-3 minutes for metal or plastic objects up to 15 minutes for porous materials. Some people spray this solution on the tree just before tapping but I have a bit more faith in the strength of trees than that.

Sap will run 4-6 weeks, but the sweetest, most sugar-filled sap will be at the beginning. Check your buckets and collect the sap every day at first as the sap will really be flowing and this will keep non-sap stuff out of the buckets. By the fifth week all the sugar that had been stored in the roots has been transferred up into the new leaf buds. Remove the spile, disinfect the tap hole, then place a bleach-treated wooden dowel in the hole.

It takes about 10 gallons of sap to make one quart of syrup, or a 40-to-1 sap/syrup ratio. Boiling it down releases a LOT of water vapor so it is best done outside. Side story: one year my dad decided to boil off the water using the stove inside the house. Mom was out of town that day. Dad boiled off approximately 50 gallons of sap which caused all the wallpaper in our house to peel. When mom got home she was pretty upset.

It's best to evaporate most of the water over a wood fire outside using a big pot. Pure water boils at 212F, finished syrup boils at 219F. Keep track of the temperature with a large candy thermometer. Once you've driven off enough water outside over the fire to raise the boiling temperature to 216F you can take it inside and finish it off over the more controlled heat of your stove. Transfer the fluid to a smaller pot, filtering it through some cheese cloth if there are solids present. Once it reaches 219F transfer the hot syrup to clean (sterilized by boiling) jars.

This syrup will stay good as-is for about two months and if frozen for up to a year. For longer-term storage it is best to reduce it down to maple sugar. To do this carefully keep boiling the syrup to drive away the rest of the water. You want the temperature of the boiling sugar to be between 290F and 300F. It will want to foam over and if it does remove the pan from the heat until the sugar/syrup settles down, then return it to the heat. Traditionally, the boiling sugar (290-300F) is transferred to a wooden bowl and stirred with a wood spoon to remove the last bit of moisture. It will harden into a solid mass as it cools. This mass is broken off the spoon and out of the bowl and stored in an airtight container. When sugar is needed use a heavy-duty cheese grater to grate off what you need.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.

Making Self-Watering Earth Buckets

Just finished these two hours ago. Meanwhile the rest of the world seems to be wrapped in blizzards. I love Houston!!

Global buckets are based on the self-watering Earth Boxes, but are made from easy to find scrap materials. I did have to buy some 1.5" diameter PVC pipe and the soil mixture for inside the buckets, but everything else was just laying around.

1. inner bucket

2. outer bucket

3. fill tube made from 1.5" PVC tubing

4. cotton cloth to wick water from reservoir to soil

5. soil (mix of peat moss, topsoil, and vermiculite)

6. gap between two buckets which acts as the water reservoir

This is the bottom of the inner bucket.

A hole approximately 1.5"-2" in diameter is cut in the center of the bottom, this is for the cotton wick. A second hole 1.73" in diameter is cut near the edge of the bottom, this is for the fill tube. A bunch of small holes (about 5/16" in diameter) are drilled randomly around the bottom of this buck to improve drainage and allow air to get to the plant roots. Sidenote: do you really think I drilled a 1.73" hole? I just cut until the tube fit.

The bottom of the fill tube has a large notch cut in it to simplify the system.

A precise person could measure (twice) and cut (once) fill tubes to the exact length needed for perfection. Luckily, plants don't need a perfect system in which to grow, so just hack a chunk out of the bottom of the fill tube, stick it through the inner bucket, and whack it off somewhere around the top rim of the inner bucket.

An overflow hole is drilled in the outer bucket.

To keep from flooding the buckets a drain hole is drilled in the outer bucket just below the bottom of the inner bucket. Hopefully you can see how I precisely measured the location for this hole.

Completed buckets before adding soil.

Now you can see all the drain holes, the fill tube and the cotton wick. The wick was made from this really hideous dust ruffle thing that I've always hated. Hopefully this hatred won't affect the plants.

Getting ready to fill the buckets.

Being lazy, I didn't feel like holding up the wick while adding the soil so I tied it to a stick. This picture is slightly misleading as the wick does end 2"-4" below the top of the soil once the bucket is filled.

Making soil.

My soil recipe is based on Square Foot Gardening and is composed of roughly 1/3 cheap topsoil, 1/3 peat moss and 1/3 vermiculite (the stuff in the wheel barrow) mixed together thoroughly. The peat moss helps hold water, the vermiculite keeps the soil loose and aerated, the topsoil gives the plant roots a place to grow. Depending on what I grow, some fertilizer may be added to the particular bucket.

And here we are back at the beginning.

It took me about four hours total to make these eight buckets and they have all been planted with different wild edibles except for the one on the end which has chard I picked up on clearance.

This is a great way to set up a container garden in a small area, especially in hot, dry locations. Another benefit of these Global Buckets is that you can move them around to optimize their access to sun or to protect them from freezing.

Once the plants are growing I'll add either a thick layer of mulch or some secondary plant like nasturtiums to shade the soil which reduces evaporative water loss. Water is added to the system through the fill tube until water flows out the overflow hole. The plants will eventually grow their roots through the holes in the bottom of the bucket directly into the water reservoir. Until then the wick keeps the soil at the perfect level of moistness.

Update January 8th, 2011: to help protect the new plants from cold weather I picked up several 12" diameter cake covers from a local "dollar store". These covers fit over the buckets perfectly, turning them into mini-greenhouses. Originally I wanted to find some sort of clear bowl, but the shape of these cake covers works better as the fill tubes don't get in the way of the covers.

Water has condensed on the inside of the covers, making them translucent rather than transparent.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.

Make a Worm Composter

Give me a Dremel tool and I'll change the world...or at least improve my backyard. Today's project is a vermiculture worm bin. I've been wanting to raise worms for a while, mainly for fishing but also for the great soil they produce from kitchen fruit/veggie scrapes.

So, worm bins. They are easy to make out of two identical, opaque plastic bins, shredded newspaper, and something that will make holes in two different sizes (1/4" and 1/16" diameter). The ideal bins would only be about a foot deep but as wide as possible to maximize the surface area. Right now Walmart, Target, Home Depot and other stores all have their "Christmas storage bins" on clearance dirt cheap (ha ha ha) so it's a great time to tackle (ha ha ha...fishing joke...worms...get it) this project. You want opaque bins as worms hate light and won't act naturally or even die if exposed to too much light.

1. inner bin

2. outer bin

3. loosely wadded up strips of damp newspaper

4. fruit/veggie waste

5. red wiggler worms

6. worm casings (aka worm poop) both in inner and outer bin

7. bricks or other thing to lift up inner bin

The key to a healthy worm bin is ventilation, hence lots of air holes are drilled in both bins. The holes in the wall of the outer bin should be 1/4" in diameter but only 1/16" in the walls and lid of the inner bin. If you use holes larger than 1/16" on the inner bin the worms will crawl out which leads to dried out worm carcasses all over. Yucky. Also drill about twenty or thirty 1/4" holes in the BOTTOM of the inner bed to allow the processed worm casings to fall into the outer bin. Occasionally you'll have a worm drop into the outer bin, too. Oh well.

Outer bin with brick risers in place. The risers raise the inner bin away from the outer bin to increase air flow to the inner bin.

There are several ways to get red wigglers, I bought mine from a bait shop. If you do this make sure you don't buy the big nightcrawlers used for bass fishing as they won't eat you kitchen waste. You'll want the smaller worms used for trout and panfish. If you don't want to buy the worms you can gather your own from the wild. Look in/under compost or manure piles or just lay some wet cardboard down on the grass for a day or too. When you lift it there will likely be a number of red wigglers under it. Even Amazon.com has jumped on the worm-wagon.

Place the worms and the media they came in in the bottom of the inner bin. If you caught them yourself then put a 1" layer of damp earth in the bottom of the bin. This soil shouldn't be dripping wet nor dusty dry. Aim for somewhat clumpy.

Worms, now home. Note all the ventilation holes.

Worm food: potato peels, lettuce, and a few other scraps.

One pound of worms will eat 1/2 pound of kitchen waste every day. Some people add their scraps every day, others collect about 3-days worth of kitchen waste before added it to the bins to minimize annoying/disturbing the worms. Do whatever you significant other tells you to do. It's just easier that way. Once you have a large, hungry horde of worms you can expand you scraps to include meat and other non-plant matter.

Newspaper layer. Yes, worms are excellent climbers.

Cover everything with 2"-3" of shredded newspaper. Cut the newspaper into 1" strips, soak them in water, squeeze them out to "damp sponge" wetness, loosely wad them up and toss them in the bin. Don't use glossy advertisements as they don't dampen well and the inks may be somewhat toxic.

That's about it. Store the bins in a dark area where they will neither freeze nor overheat. They can handle temperatures close to 30F and as high as 100F but will stop breeding at these temperatures. Under ideal conditions your worm population will double every 90 days. Note that like with every other creature, worms don't like living in their own excrement. You'll have to empty the inner bin about every 4 months to keep your worms healthy. Worm casings are loaded with beneficial microbes and nutrients vital to plants, often having five times as much nitrogen, seven times as much phosphorus, and eleven times as much potassium as ordinary dirt, making it a wonderful natural fertilizer.

Worm bins should have a nice, earthy smell to them. If an unpleasant odor is noticed you've probably been overfeeding the worms. Don't add any scraps for several days until the current material has been consumed. Also check that your system isn't too wet. If it is more than just damp add some more shredded newspaper to absorb excess moisture. My problem in Houston is the system drying out so I keep a spray bottle of water next to the bin to dampen the newspaper as needed.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.

Fermenting Texas

"I drink and I know things."

-Tyrion Lannister

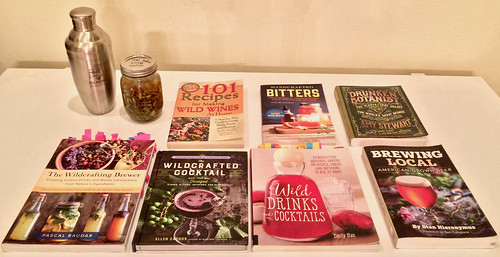

The use of wild plants to produce alcohol or add flavors to alcoholic beverages goes back into prehistoric times. These are the books I recommend to help you tap your inner cave bartender!

#1 is definitely Pascal Baudar's The Wildcrafting Brewer. This is pretty much the bible of all things wild and fermented, from where to get your wild yeasts, what plants to combine with these yeasts to create alcohol, and how to blend the flavors to make fermented beers, wines, meads, and whattzits that will make people rave.

#2 is the amazing mixologist Ellen Zachos with her book The Wildcrafted Cocktail. If you want to know how to make delicious cocktails by mixing your foraged finds with traditional hard liquors and spirits, this is the book you want.

#3 is Emily Han's Wild Drinks and Cocktails, the book that started me off into the fascinating world of foraged drinks. This book covers the switchels, shrubs, and squashes which were the "cocktails" of the prohibition era. These types of drinks are being rediscovered by top-level bartenders due to their fascinating history and fantastic flavors!

#4 is Stan Hieronymus's Brewing Local. I was actually one of the technical consultants on this book which covers the history of beer in North America. The early Germany settlers made beer out of damn near EVERYTHING the grew and this book tells you how you can, too!

#5 is John Peragine's wonderful 101 Recipes for Making Wild Wines at Home. As much as I love beer, wine is much simpler to make and so it fits my busy life.

#6 is Ken Schramm's The Complete Meadmaker (not shown in picture, lent it to friend). I have a real sweet tooth and access to honey which is good because mead is my favorite fermented drink thanks to Viking ancestors.

#7 is Will Budiaman's Handcrafted Bitters. Bitters are the magic ingredient that turn a mix of alcohol and fruit juice into cocktails. There's a whole world beyond Angostura Aromatic Bitters!

#8 is Amy Steweart's The Drunken Botanist which covers all the history of the plants used to make those alcoholic drinks y'all love so much. It's a hysterical and somewhat scary book when you realize where the fine line between tasty and poisonous lays!

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.

Podcasts

- School of Outliers - Jungian Shadows, Foraging, and Shamanism

- A Talk on the Wild Side - Why Forage?

- Voyage MN Magazine - Rising Stars!

- Lavender Water - Touching Grass

- Women In Agriculture - Foraging is Freedom

- Truth Tastes Funny - Evolution and Civilizational Collapses

- Georgia Bushcraft - 5 Plants for Hygiene

- Texas A&M AgriLife Plant Party - Good Medicine from Hated Trees

- Texas Co-op Power Magazine - The Grazing Craze

- Talking Sh*t With Beecher - Human Evolutionary Constructs

- Healing For The Soul - Caveman Connections

- Girls Throw Too - Better Brain Health by Throwing Things at Stuff

- Georgia Bushcraft - 5 Easy Plants for Vitamin C

- Teach 2 Dumb Guys - Plants in Space

- The Fluffy Hobo - Mushrooms, Ecology, and Space

- Georgia Bushcraft - Top 5 Beginner Wild Mushrooms

- American gypC - Easy Caveman Activities for Health

- Unpacking the Outdoors - Health Benefits of Being Outside

- Herb Society Houston - Identifying & Using 8 Wild Mushrooms for Beginners

- DTRH Podcast - Go Wild, Get Healthy

- The Vibes Podcast - Cavemanosity

- Label Free Podcast - The Caveman & the Beauty Queen

- Georgia Bushcraft - Top 5 Medicinal Plants for Bushcrafters

- Texas Monthly Magazine - 11 TX Plants You Didn't Know You Could Eat

- Texas Monthly Magazine - The Joy of Foraging My Own Food

- TalkShopLive - The Blood Pressure Pill

- Nature Reliance School - Living Wild

- Konversations With Kenny - Ancestral Health Tips

- The Journey Is Real - Be Ancient, Live Long

- TalkShopLive - The Brain Pill

- New Bridge Radio - Better Living Through Foraging

- Culinary Libertarian - Fermentation 101

- Josh Boone Show - Agriculture Sustainability

- Wise Traditions - Healing Properties of Medicinal Plants

- TalkShopLive - The Libido Pill

- AgeUcational - Foraging for Brain Health

- Dying to Live - When Your Life Rx is Right On

- What's Up with DJ - What is Cavemanosity?!

- Health in the Real World - Living off the Land

- Undefined with Keagan Bouwer - Living Like a Caveman, Foraging, & Mushrooms

- Chef Grace's Place - Wild Foods!

- Houston Museum of Natural History - Beyond the Bones: Wild Edibles and More

- Drink and Grow Rich: The Past, Present, and Future of Humans

- The Muscle Maven: Ginger for Pregnant Women and New Mothers

- People Explained: How Living Off the Land and 'Acting Ancient' Improves Your Health

- STACKED with Coach Joe DiStefano: Medicinal Plants & The Health Benefits of Foraging

- True Stories & Science with Evin Weiss: The Little Known Secrets To Poisonous Plants

- Chase Your Dreams - The Medicine Man

- 10 Minute Leaders: Leadership Tips From a Forager

- Happiness is Easy: What Would a Caveman Do?

- Dr. Stephanie Schuttler, The Fancy Scientist: Sustainable Foraging

- Jaded 80's Baby: The Co-Evolution of Humans and Plants

- Land Ethic: Both Science and Legend are Valid Models of Nature

- I Know You: Lost in the Woods?

- The Garden Path: Kitchen Garden Medicinal Plants

- Mothering Earth: Do's and Don't of Foraging

- Epic Gardening: Herbs and the Immune System

- Epic Gardening: Elderberries the King

- Epic Gardening: Echinacea the Queen

- Epic Gardening: Garlic the Knight

- Epic Gardening: Turmeric the Bishop

- Epic Gardening: Heal's All the Magician

- Epic Gardening: Make & Use Herbal Preparations

- Wazoo Survival - Skills: Into to Foraging

- Wazoo Survival - Skills: Ham Radio

- Feeding Fatty Podcast (2/1/2021)

- Culinary Libertarian 11/16/2020

- Culinary Libertarian 2/18/2019

- The Prepper Website 12/28/2020

- "Hear Our Houston" audio walking tour

- In the Rabbit Hole Audio Podcast

- Your Harris County 9/29/2020

- The Garden Path Podcast (3/21/2018)

- Off the Grid News Podcast April 2017

- Prepper Broadcast Audio Podcast #1

- Appleseed Radio Audio Podcast (starts at 23 minutes in)

- Houston Public Radio Foraging Interview

- Natural Dallas Foraging Interview

Privacy & Amazon Paid Promotion Statement

I use third-party advertising companies to serve ads when you visit this website. These companies may use information (not including your name, address, email address, or telephone number) about your visits to this and other websites in order to provide advertisements about goods and services of interest to you. If you would like more information about this practice and to know your choices about not having this information used by these companies, click here.

I participate in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for me to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites. The prices you pay for the item isn't affected, my sales commission comes out of Amazon's pocket.

*These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease.