Abundance: common

What: leaves

How: seasoning

Where: sandy soil along woodland borders

When: spring, summer

Nutritional Value: low

Dangers: use sparingly as a herb as high doses can be poisonous. ~1% of the population suffers an allergic reaction to epazote

Young epazote plants.

Top view of epazote plant.

3/4 tilt view of epazote.

Side view of epazote. Note the alternating leaves.

Close-up of epazote's hairy stem.

Topside of leaf. Note how the veins run to the points along the edge of the leaf.

Underside of the leaf. Note how the veins run to the points along the edge of the leaf.

Epazote flowers.

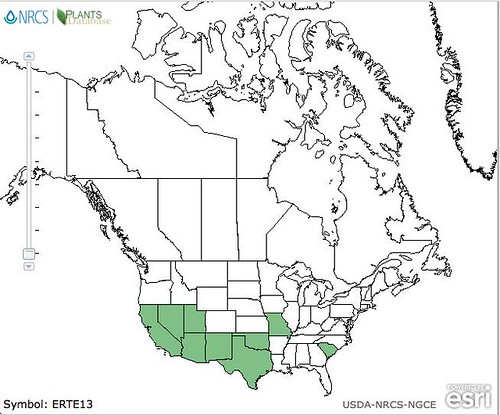

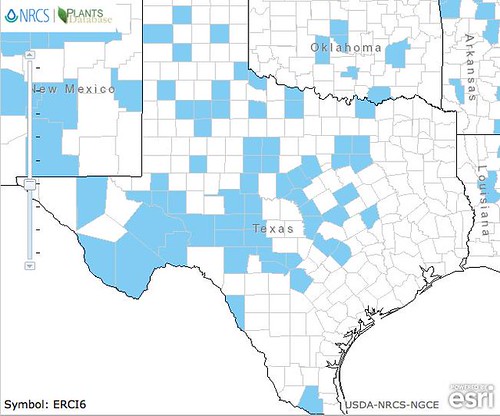

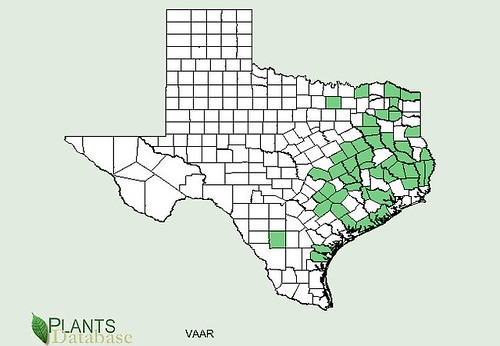

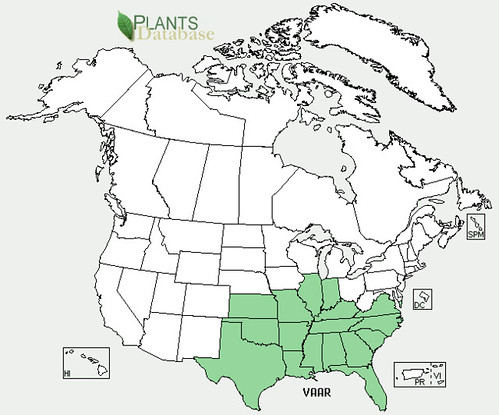

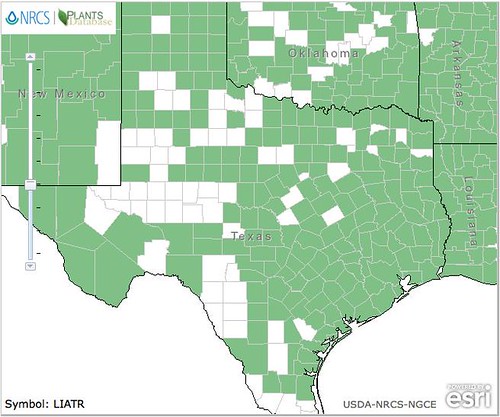

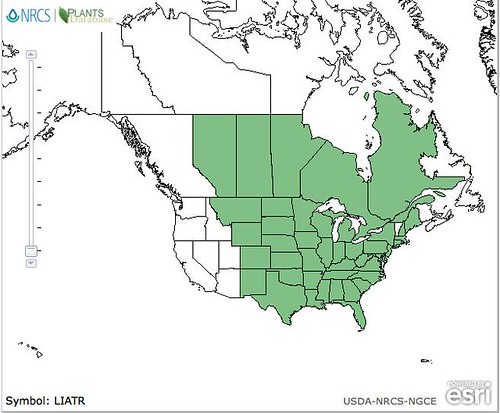

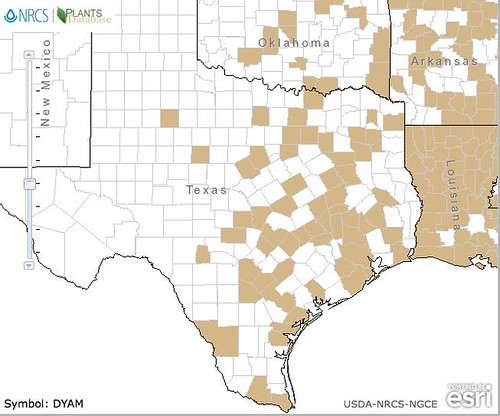

Texas distribution, attributed to U. S. Department of Agriculture. The marked counties are guidelines only. Plants may appear in other counties, especially if used in landscaping.

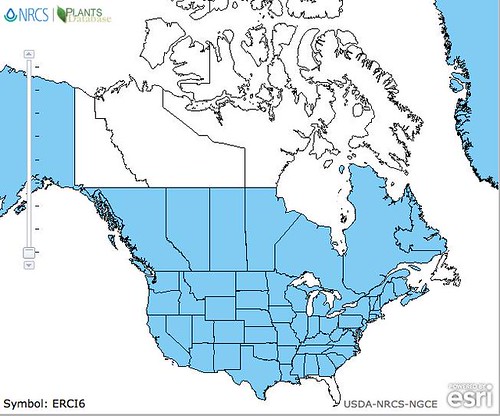

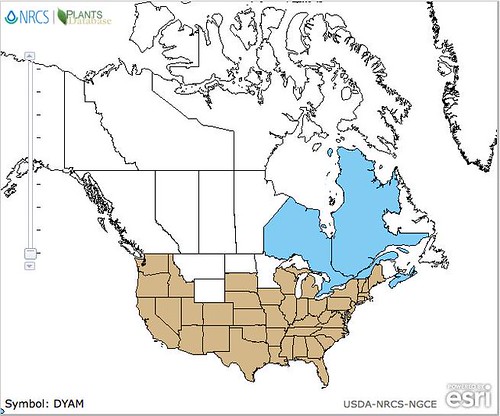

North American distribution, attributed to U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Disturbed, sandy soil along woodland borders is the most likely place to find the ancient herb. If you are familiar with lamb's quarter's appearance you're half way to identifying this plant. Epazote leaves alternate up the stem and look like elongated versions of lamb's quarter leaves. This plant will branch out some, usually from near the bottom of the plant. Trimming its top will cause multiple sprouts continuing to grow from the cut spot. By the end of its growing season it can be five feet tall and somewhat leggy. The most distinctive part of this plant is its scent. To me the crushed leaves smell like lemons soaked in gasoline. Other people think it smells more like brake fluid or some sort of industrial cleaner. It's hard to believe something who's name translates into "skunk sweat" is used heavily in cooking! But throughout the ages it has been a key flavor in South American dishes, especially in the areas of the Yucatan and Veracruz areas of Mexico.

Considering how strong of flavor it has only a few leaves are needed to impart the correct citrusy tones to bean dishes. Why is it added to beans? Well, it turns out Epazote contains some compounds that are particularly good at breaking down bean proteins, making them more readily digested by the human body. A side effect of this "pre-digestion" is the gas-producing effects of beans is reduced. The leaves can be dried but fresh is preferred when cooking.

Epazote flowers and seeds resemble those of lamb's quarter, with the flowers being tiny, green, and numerous and the seeds being tiny and brown. Due to the high concentration of ascaridole in the seeds, I don't recommend eating them like lamb's quarter seeds.

The ascaridole oil found in Epazote leaves is used as a deworming (vermifuge) agent and was taken as a tea made from the leaves and seeds to rid the humans and animals of tapeworms, ringworms, and other parasitic worms. To expel the dead worms from the body, a laxative was also taken. However, the levels of this oil needed to kill worms is very close to what would be fatal to humans, too. This makes Epazote an anti-worming agent of last resort, modern medicines are much safer.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.