Scientific Name(s): Hibiscus syriacus

Abundance: common

What: flower buds, flowers, tender seed pods, seeds

How: flowers - raw; flower buds & young seed pods - raw or cooked like okra; seeds - roasted for coffee substitute

Where: landscaping - full sun, well drained soil, neutral pH

When: summer

Nutritional Value: antioxidants, mucilage

Dangers: noneMedicinal Summary: mucilage in flowers binds to glucose in the GI tract, slowing/stopping its passage into the blood

Leaf Arrangement: Leaves are arranged alternately along the stems, with each leaf emerging singly at a node.

Leaf Shape: Leaves are broadly ovate to rhombic-ovate, typically 1 1/2" to 3 3/4" long and 1" to 3 1/2" wide, often displaying three distinct lobes.

Leaf Venation: Venation is palmate, with three primary veins radiating from the base of the leaf blade.

Leaf Margin: Margins are coarsely crenate to serrate, featuring rounded to sharp teeth along the edges.

Leaf Color: Leaves are medium to dark green on the upper surface and lighter green beneath, with a slightly glossy appearance.

Flower Structure: Flowers are solitary and axillary, measuring 2 1/2" to 4" in diameter, with five broad, overlapping petals forming a funnel shape.

Flower Color: Petals range from white to pink, lavender, blue, or purple, often with a contrasting dark red or maroon throat.

Fruit: The fruit is an ovoid capsule, approximately 3/4" to 1" long, composed of five valves that split open at maturity to release seeds.

Seed: Seeds are kidney-shaped, about 3/16" to 1/4" long, with a smooth surface and a fringe of reddish-orange hairs along the margin.

Bark: Bark is light gray to gray-brown, smooth on young stems, becoming slightly rougher and fissured with age.

Hairs: Young stems and leaf petioles are sparsely to moderately covered with minute stellate hairs, which diminish as the plant matures.

Height: This deciduous shrub typically grows to a height of 8' to 13' and a spread of 6' to 10', forming an upright, vase-shaped habit.

Rose of Sharon flower color is somewhat temperature dependent, range from blue when cooler and white when hotter.

Unopened flower buds are a tasty treat,

Rose of Sharon leaves are toothed and also often have three lobes.

Rows of brown, 2mm-diameter seeds are found in the dried seed pods.

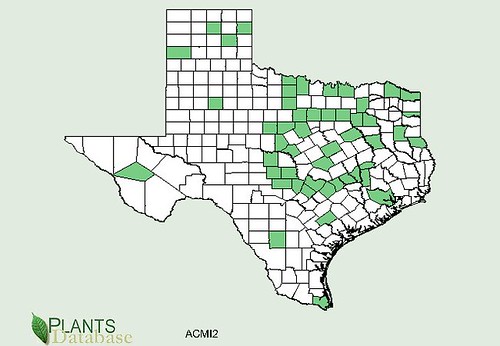

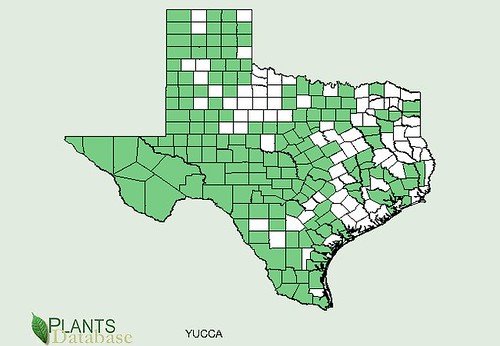

Texas distribution, attributed to U. S. Department of Agriculture. The marked counties are guidelines only. Plants may appear in other counties, especially if used in landscaping.

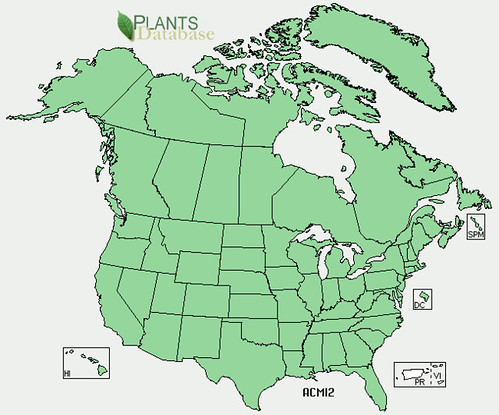

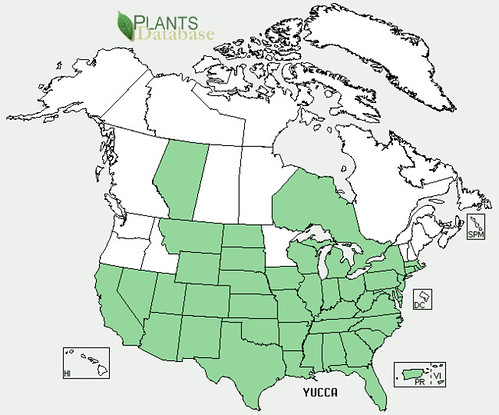

North American distribution, attributed to U. S. Department of Agriculture.

Rose of Sharon are a non-native member of the mallow (hibiscus) family originally from East Asia, but its striking blossoms have made it a landscaping favorite across the Southeastern United States. This large shrub can reach up to 14' in height, but winter frosted often kill branch tips, preventing them growing that tall.

The showy flowers are loaded with an assortment of antioxidants including carotenoids anthocyanins, and flavonols. These compounds give the flower petals their color and their concentrations are dependent on soil pH and nutrients, but the red anthocyanins are sensitive to temperature, breaking down during the hotter times of day, allowing the yellowish/orange carotenoids or blue/purple flavonols to show. This causes flowers to change color throughout the day or across the short, 2-3 day, individual blooming time. While the life of a single flower passes quickly, the bush constantly produces new flowers for several months.

Technically, the leaves of Rose of Sharon are edible, but I find them somewhat tough. But the flowers, from young buds, through opening, to tender seed pods, are wonderful. All of these stages are fine raw, but the closed flower buds and young seed pods can also be pickled or fried just like okra pods. If left to reach full maturity, the seeds collected from the dried pod can be roasted, then ground up and used to stretch out one's supply of coffee. They don't contain any caffeine, but they do have something like a coffee flavor...especially if you haven't had coffee in a while.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.