Abundance: common

What: mushroom

How: tea, tincture

Where: dead trees

When: spring, summer, fall, winter

Nutritional Value: medicinal

Dangers: while not poisonous, the from the mimic False Turkey Tail crust mushroom (Stereum ostrea) don't taste as good.

COLLECTING MUSHROOM REQUIRES 100% CERTAINTY. WWW.FORAGINGTEXAS.COM ACCEPTS NO RESPONSIBILITY FOR IDENTIFICATION ERRORS BY ANY READERS.

Turkey Tail mushroom clusters. Many different colors are possible.

Close-up of top of Turkey Tail mushroom. This one is slightly larger than a US quarter coin.

Close-up of bottom of Turkey Tail mushroom. This one is slightly larger than a US quarter coin.

MIMICS!

Topside view of False Turkey Tails mushrooms (Stereum ostrea).

Underside view of the "crust" covering most of the dead log. This crust has a smooth surface and lacks the pores of Trametes versicolor

The underside of mimic Gilled Polypore (Trametes betulina) has gills rather than pores underneath. Don't eat/drink it.

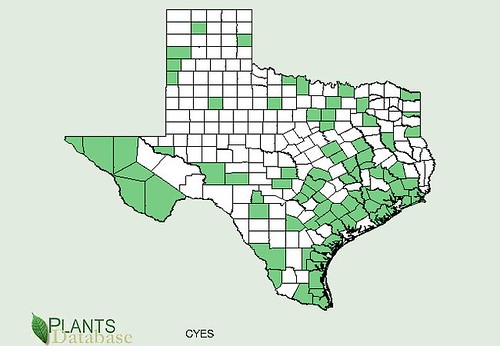

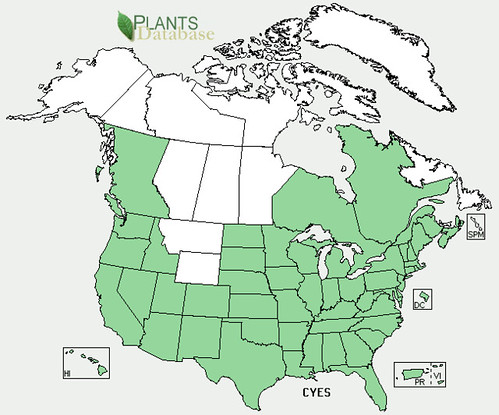

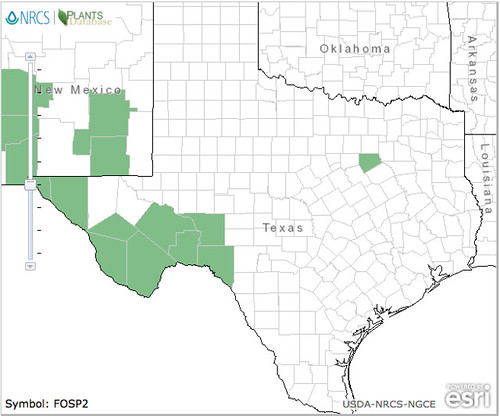

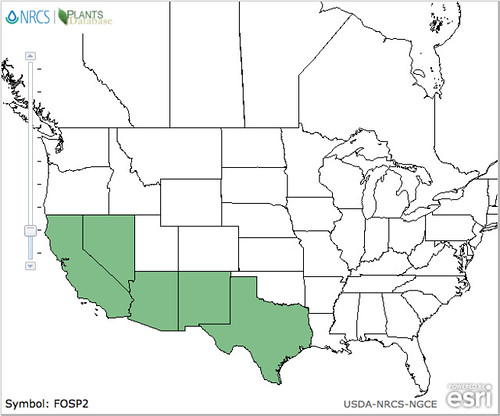

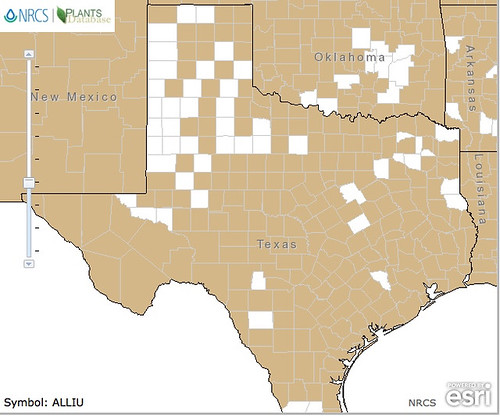

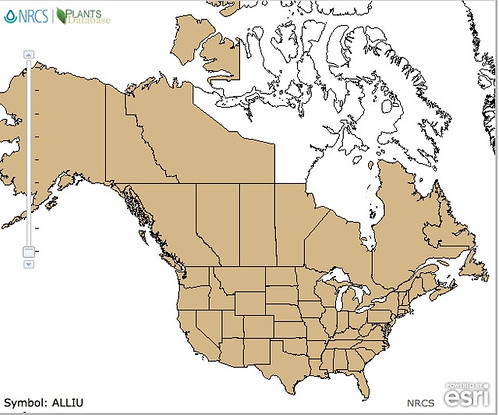

North American distribution, attributed to U. S. Department of Agriculture.

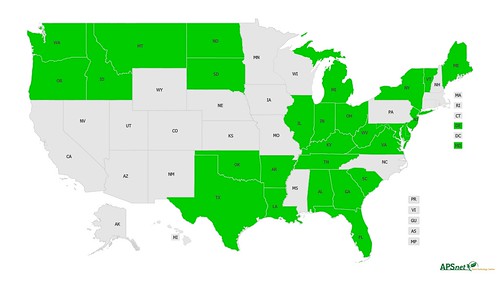

The only public lands in Texas you can legally harvest mushrooms are National forests and grasslands. Check the rules and regulations for your state to stay out of trouble. Some national forests require you to purchase a mushroom harvesting license.

Turkey Tail mushrooms are one of the most powerful wood decomposers in the forest and can be found on just about any dead tree. When young and fresh they really do look like the multicolored, striped fan-shaped tails of turkeys. They have bands of red, brown, white, and gray as well as yellow and even purple. They often grow in thick, overlapping patches on dead hardwood and softwood trees though the mushrooms themselves are quite thin.They will grow parallel to the ground and have a slight bowl shape with the lowest point being its attachment to the tree. They will be fan-shaped ranging from half-circles to almost full circles. They give white spore prints.

There are several very similar mushrooms so to be sure you have Turkey Tails ALL the following details must be met:

1. They are polypores. Turkey Tails will not have gills on their underside but many tiny pores from which spores are released.

2. These pores are extremely small but still visible to normal eyes, numbering 3-8 per millimeter. A magnifying glass helps see them properly. If only 1-3 pores per millimeter you have some other Trametes species

3. The topside feels velvety/fuzzy due to many tiny hairs. A magnifying glass will also help to see these hairs.

4. Is the top of the mushroom white to grayish? If so, you do NOT have a Turkey Tail but likely the related, Trametes hirsuta, species.

5. Do the colored zones blend/run together or do they have sharply-defined boundaries? If not sharply define it is likely you have Trametes pubescens.

6. The mushroom must be flexible yet thin. Stiff mushrooms are probably Trametes ochracea.

Turkey Tail tea has a lovely mushroomy flavor. Collect five fresh mushrooms about the size of a quarter. Chop these up and boil them in one cup of water for ten minutes. After boiling them ad a bit of cold water to bring the volume back up to one cup. Strain out the mushroom bits (don't eat them) then drink it once it has cooled off enough to imbibe safely.

Scientific studies have shown Turkey Tail mushrooms contain a number of anticancer and antibiotic compounds, though this information is NOT to be considered medical advice.

Tea made from the fresh mushrooms is a traditional method of accessing these medicinal molecules. Also, an alcohol extract of Turkey Tails can be used to access the medicinal properties of these mushrooms. Half-fill a jar with chopped/shredded Turkey Tails then add enough vodka or other 100-proof alcohol to cover the mushrooms with 1" alcohol above the mushrooms. Tightly cap then vigorously shake the bottle. Shake it 1-2 times a day for six weeks then strain out any mushrooms solids. Place the filtered tincture in a colored, stoppered bottle and store in a cool, dark place. Traditionally, 3-5 drops of this tincture would be taken daily, though do NOT consider this medical advice.

Often the alcohol-extracted mushroom material was then be boiled in water to extract any water-soluble medicinal molecules. Starting with twice as much water (by weight) as mushrooms, this was boiled down to half. The decoction was allowed to cool, solids were strained out, and then added to an equal amount of the alcohol tincture. This gave a solution that was 25% alcohol which was enough to preserve it. The dosage of this solution was still 3-5 drops a day.

A comprehensive review of the medicinal properties, including many scientific journal referneces, of Turkey Tails mushrooms can found in MycoMedicinals.

When identifying mushrooms always cross reference them with several books to achieve the proper level of certainty. I'm not trying to sell you books, I'm trying to help you avoid a mistake.

Buy my book! Outdoor Adventure Guides Foraging covers 70 of North America's tastiest and easy to find wild edibles shown with the same big pictures as here on the Foraging Texas website.